Language & Reality

From the little I know about linguistics, the most interesting idea I’ve found is the Whorf-Sapir Hypothesis. In simple terms: to what extent does language shape how we think? My introduction to the idea was Benjamin Lee Whorf’s work on the subject.

Though the strong form of the argument, that language determines how we think, has been largely rejected by linguists, there’s strong evidence that the fundamental structure of the languages we speak shapes the ideas we tend to have.

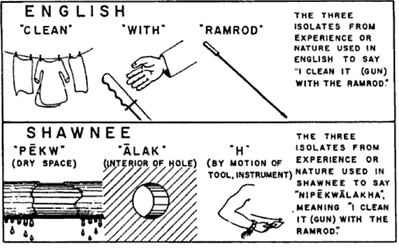

Whorf illustrated insights from his study of American Indian languages, which are interesting precisely because they are as different as a language could be from Indo-European languages. The reason that language shapes thought, according to Whorf, is that languages break down ideas into vastly different component parts. And not just subtly different nouns and verbs, but completely different conceptions of “noun” and “verb”:

Probably the most puzzling idea Whorf described at length in his work was that some languages don’t even have the concept of time. The Hopi language, apparently, conceptualises time and space in a deeply interrelated way, where there is no clear way to distinguish what we in the Indo-European universe separate into time and space. Instead, there is what is real, present, has unfolded, nearby and what is distant, unobserved, mental (idea) - or something along those lines.

--

Growing up speaking Russian, then learning English and more recently some German, I took a lot for granted. Despite the grammar differences and obviously distinct vocabularies, if you're only ever exposed to Indo-European languages, certain things feel universal. The idea of words and sentences. The expectation that concepts map onto sequences of characters. The rising tone that signals a question.

I'm learning Chinese and it's breaking many assumptions I previously had about language.

For example, there's no clean concept of "words" as we know them. Instead, you glue together symbols with individual meanings: 女 (female) + 人 (person) = 女人 (woman). Or: 生 (to produce) + 气 (air) = 生气 (to get angry - to puff up, essentially). It's surprisingly logical. Even large compounds like 兄弟姐妹 (older brother + younger brother + older sister + younger sister = siblings) aren't hard to pronounce because each symbol corresponds to a single syllable, and Chinese syllables are even faster to say than most Western ones.

Sentence-building works differently too. In every language I'd spoken before, you form questions by changing word order and adding a rising, inquisitive tone. In Chinese, you simply add particles to the end of a statement. Verbs don't conjugate for tense either. Take 健身 (to work out - literally "strong body"). Add 在 and you get 在健身 (working out, or "in the process of strong-bodying"). The same character 在 also means "at" for locations. Then there's 了, which signals completion: 健身了 means "worked out," or more literally, "strong body achieved." It carries a subtly different philosophical flavor than Indo-European past tense - a sense of something having been accomplished rather than simply having occurred - though practically it means the same thing.

It's fascinating to pop the linguistic hood of a society by learning its language. Chinese feels like a parallel world that developed from different starting conditions and landed on a completely different conceptual configuration - different conceptual building blocks entirely. It's no surprise this contributed to such a cultural chasm between East and West. And yet, these different languages ultimately arm different people with the tools to express an essentially constant human condition.

other essays: